In 1960, the US company Texas Instruments attracted attention. Jack Kilby developed the world’s first integrated solid-state circuit – a “chip into a new world of technology”. Even in the largely closed German Democratic Republic (GDR), this news did not go unnoticed. The physicist Werner Hartmann immediately recognized its significance and said that there should be no hesitation in the field of microelectronics. The political leadership of the GDR took a slightly different view and focused on nuclear physics instead. Hartmann, however, persisted and finally achieved his first partial success on August 1, 1961. Microelectronics came to Saxony for the first time with the founding of the Molecular Electronics Center (AME) in Dresden-Klotzsche. The beginning of a fascinating story, the end of which is still far from being in sight today.

1960 to 1990: The beginnings of microelectronics in the GDR

With seven employees, Werner Hartmann began a race to catch up in 1961 that was never to be won. Although the number of his colleagues grew steadily, it would take until 1968 before the first major success was achieved – the preparation of the GDR’s first solid-state switch circuit, the C10 with seven transistors. Despite this and numerous other impressive achievements by the creative and innovative Hartmann team, microelectronics remained a poor relation in East Germany. When Erich Honecker succeeded his predecessor Walter Ulbrich as SED chairman in May 1971, investment in microelectronics was cut back considerably – despite all that had already been achieved, including in the area of foreign currency procurement. Hartmann nevertheless remained ambitious and expanded “his” AME to 950 employees by 1974. However, the mistrust of the State Security in his person had long since been aroused. In June 1974, Hartmann was suddenly put on leave and was even banned from working at AME. Although there was never any evidence of misconduct, let alone espionage, the father of East German microelectronics was sidelined. Hartmann died in 1988, even before the political turnaround.

The AME, on the other hand, was renamed several times and finally continued to operate under the name “Zentrum Mikroelektronik Dresden (ZMD)” until the fall of communism in 1990 and beyond. ZMD celebrated its greatest success in the East with the development of the GDR’s first megabit chip. However, ZMD’s masterpiece was never produced. The necessary machines were not available. In the end, the company had more than 3,300 employees in the year the Wall came down. All the bright minds that were encouraged and challenged in the times of scarcity and the planned economy in Dresden remained as a great legacy. They were also the ones who made Saxony interesting for Western microelectronics. An asset that, several years later, was to make Saxony the microelectronics hotspot in Europe. ZMD also remained in Saxony to a certain extent, and is now owned in part by the Japanese group Renesas Electronics and in part by the company X-FAB. Both are still active in Dresden.

1990 to 2023: From a lighthouse to the microelectronics region of Europe

In the Free State of Saxony, the policy of so-called “clusters” or “lighthouses” was already being pursued shortly after the political transition, in 1990. The inventors, or rather inventors, of this special type of company relocation policy were Saxony’s then Prime Minister Kurt Biedenkopf (born in the Palatinate) and his Finance Minister Georg Milbradt (born in the Sauerland) – both West German politicians. Their flagship project was the Dresden region. The Saxon state capital was to become a flourishing location for national, European and international semiconductor companies.

The “lighthouse policy” was a highly controversial concept at the time and had to withstand some criticism. Regional politicians accused the Saxon state government of unilaterally favoring the state capital. Chemnitz and Leipzig would fall behind, not to mention the rural areas. But the concept worked and, from today’s perspective, was as clever as it was far-sighted. After all, it combined Saxony’s strengths and potential with the wishes of the high-tech sector. After all, the latter was looking for suitable locations, especially in the post-reunification period, to drive forward its expansion into the East and thus into new lucrative markets.

With ZMD and the more than 3,000 semiconductor experts in the region, there were already good arguments in favor of Dresden. It was also home to the Technical University of Dresden (TU Dresden), an excellent university that experienced rapid development after 1990. For example, the Faculty of Computer Science and the Faculty of Electrical Engineering were founded at TU Dresden in 1991. Further good arguments for the region, apart from the typical Saxon persistence with which even the naturalized Biedenkopf and Milbradt promoted their location.

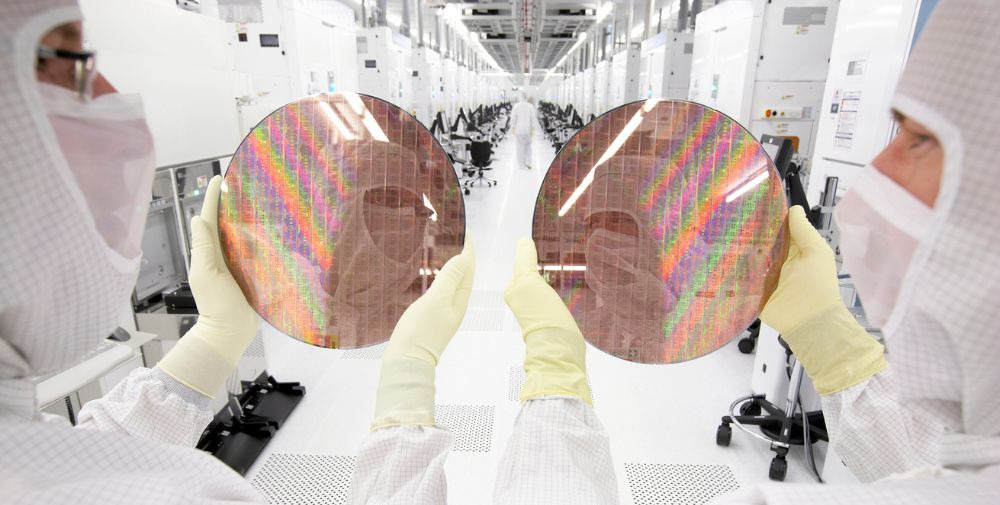

With SAW Components in 1993 and Siemens in 1994, the first two semiconductor companies opened a site for microelectronics production in Dresden. They were not to be the last. Today, the former Siemens plant operates under the name Infineon and employs around 3,500 people. In 1996, the US company Advanced Micro Devices (AMD) founded its subsidiary AMD Saxony LLC & Co KG in Dresden and built a processor production plant on the outskirts of the Saxon state capital. A second AMD plant finally followed in 2005. In 2009, the newly founded GlobalFoundries Inc. took over the two fabs. GlobalFoundries is a pure contract manufacturer and now employs over 3,000 people at its largest plant in the world in Dresden.

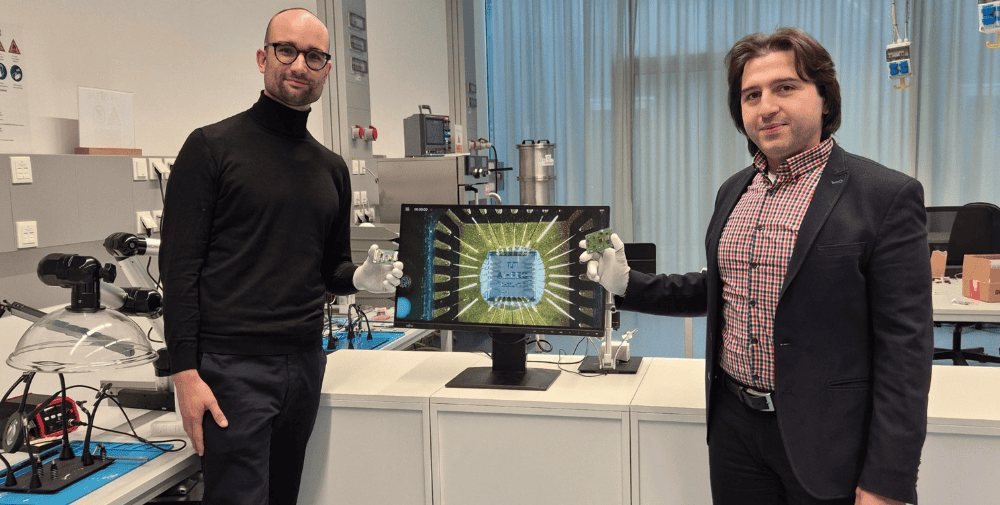

An ecosystem has developed around these first fabs that is unparalleled not only in Germany, but also throughout Europe. Hundreds of service providers and suppliers settled in the Dresden region in particular. Medium-sized companies that still form the backbone of the East German economic and industrial landscape today. In and around Dresden, a value creation network was formed that is almost complete and therefore unique. Whether masks, wafers, machines and systems, software, chip design or chemicals – Saxony has become the Mecca of semiconductor technology.

In June 2021, the next major triumph finally followed for a region that has created the perfect conditions for semiconductor manufacturing since the fall of communism in 1990. In a global competition, Dresden came out on top against strong competition from Singapore and New York. After impressive years of growth for the cluster, the next major plant, Robert Bosch Semiconductor Manufacturing, settled in the north of Dresden. Hundreds of suppliers and service providers in the region now also offered the perfect conditions for Bosch. Today, 500 associates are employed at Dresden’s newest plant.

The EU Chips Act in 2023 was followed by a real investment push. Infineon (€5 billion), Jenoptik (€70 million) and the Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company (TSMC) in cooperation with Infineon, Bosch and NXP (€10 billion) all announced new plants in Dresden. GlobalFoundries is also currently looking into expanding what is already the world’s largest fab. It seems certain that this will not be the last investment in the location. Today, Dresden is the largest and most successful microelectronics region in Europe. Every third chip manufactured in Europe comes from here. The foundations for this were laid in the 1960s by a visionary and seven employees. A small beginning that developed into something great.

__________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

This article was first published as part of our NEXT magazine “In Focus: Microelectronics”

👉 To the full issue of the magazine

Image: GlobalFoundries