The DS-GVO as a deterrent for further EU regulations

Politicians, in any case, as much is certain, have heard the past calls for more control quite interested and feel increasingly in the duty. Good news for some. A horror for the others. For some time now, Europe in particular has been rolling over with the adoption and publication of more and more new “acts”. Whether AI Act, Digital Services Act, Digital Markets Act or now the Data Act – the digital space and the digital industries are looking at a veritable flood of upcoming bureaucratic interventions these days. That these “acts” aim to make things better is undisputed. But they also carry the risk of getting out of hand. Complicating things. To scare off innovators or drive them out of their own sphere of influence. A good example of this is still the introduction of the DS-GVO. “Companies in Europe today face a confusion of interpretation between member states, but also within individual countries. Even in Germany, each individual state data protection authority can represent and enforce its own legal interpretation. This legal uncertainty leads to a locational disadvantage, especially for small and medium-sized enterprises,” the digital association Bitkom still rightly warns in this environment.

How is the handling of data to be controlled when vast amounts of new ones are created every day?

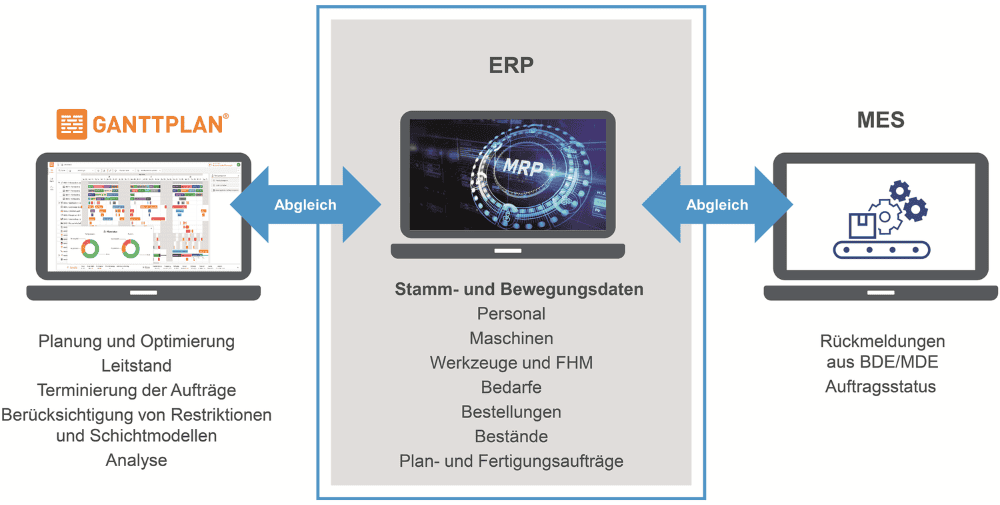

With the Data Act of the European Union, Europe’s latest regulatory offshoot has now seen the light of day. Enthusiasm is, one might have guessed, limited. Too much for some. Too little for others. Only the EU and the representatives:of the people active here seem happy. Finally, another thick board is pierced, even if not handsome, functional and thought through to the end. But how is this to succeed in this confusing area representatives:inside, who are just as overwhelmed as the end consumers:inside, whom they are trying to protect. Because yes, data is the “new oil” of the present. But it exists in unbelievable quantities. And no less unbelievable amounts of data are added every day. So how is regulation supposed to work here? How do we control it? How the targeted trade? Already in the course of our new hybrid themed magazine NEXT “Smart Systems”, AI expert André Rauschert pointed out in a video interview that, especially in the production sector, data is collected and stored on a daily basis that no human being can keep track of without technical assistance – for example, in the form of AI systems. A machine with up to 3,000 sensors produces terrabytes of data per day. And from the giant wind turbine to the small smartwatch, there are millions of devices, plants, machines and systems. Only a few with the sensor density mentioned, admittedly. But all with enough “sniffing” to fill data by the heap into cloud and local data storage.

Consumers:inside are supposed to be protected, but they lack oversight and insight

It therefore seems almost cute when it says “Owners of Internet-of-Things devices should be able to share their data with third parties in the future”. As if they haven’t been doing that for a long time, even if not consciously and voluntarily. Navigation providers, for example, work with the traffic data of their users. Fitness tracker manufacturers with vital data. Car manufacturers with accident and vehicle data. Streaming services with the usage behavior of their subscribers. Even smart home applications have been caught recording conversations and activities of unknowing owners. And all of this, and much more, should be subject to government control in the future? Should it be shared, traded, and used together? The goal of giving consumers more control over their lives, their data and their privacy is laudable. But how are laypeople supposed to keep track of this jumble of data producers and data octopi that have existed for a long time and use it for their own benefit, or at least control it? The goal of disclosing data in real time with the “Data Act” is just as noble. However, with dozens of Internet-capable devices in a household, data volumes from a wide variety of manufacturers come together here that are likely to overwhelm even experts in the field. The consumer looks at the end like the proverbial pig in the clockwork.

The industry fears important know-how to lose and/or disclose

And also manufacturers of appropriate devices threaten the overloading. In principle, a separate contract would have to be concluded for each device with each user on the use of data. Even a glance at the current data protection and data use agreements on classic Internet sites shows the dilemma. No one who is not legally trained can actually see through this. And in the wake of the “Data Act,” there is a threat of further overload. Especially since the purposes for which data may be collected have not even been defined in the current Data Act. On this basis, only absolute data experts are likely to be in a position to actually protect their data, to trade with it, and to avoid being taken advantage of. The industry, for its part, has its own sensitivities and fears that this social data experiment will make it even easier for Europe’s know-how to be lost to competitors and illegal data collectors. It is not for nothing that companies like SAP and Siemens are already vociferously criticizing the “Data Act.” After all, aside from end-customer data, government actors could also directly access companies’ data files if an “emergency” such as a forest fire or other disaster made it necessary. A rogue who thinks evil of this.

Before 2026, the “Data Act” will have no effect

Not least, there is the question of how data will be standardized, made readable and accessible in real time. If there is one thing the industry has struggled with internationally so far, it is finding uniform standards and rolling them out across the board. Not only would devices have to transmit standardized data. The corresponding cloud systems of different providers would also have to function in a uniform manner. All companies that offer devices, equipment, plants, machines or data-based systems in Europe are affected. The major cloud providers in particular, such as Google, Amazon and Microsoft, would have to make major improvements. As understandable as it is to make it easier for end customers to switch from one cloud service to another in the future – similar to a telephone provider – it will be exciting to see how the big players in the industry plan to deal with this new challenge of protecting their customers’ data and making it accessible at the same time. Like its Act “brothers and sisters,” the Data Act is still no more than writing on patient paper. The Data Act is expected to be formally endorsed in the fall, to take effect 20 months later. Following that, manufacturers and vendors would have one year to comply with the new requirements. Accordingly, this regulation balloon won’t go up before 2026. Nor is it unlikely to burst by then. After all, technology regularly overtakes tough political processes.

So all half bad? Time will tell.

Continuing links

EU lashes out on “Data Act”

Data Act: Council and Parliament reach agreement on fair data access and use

EU states and EU Parliament agree on data law

New data law: EU earns criticism for “Data Act”

EU states and EU parliament agree on data law

EU wants better use of data

Money against data