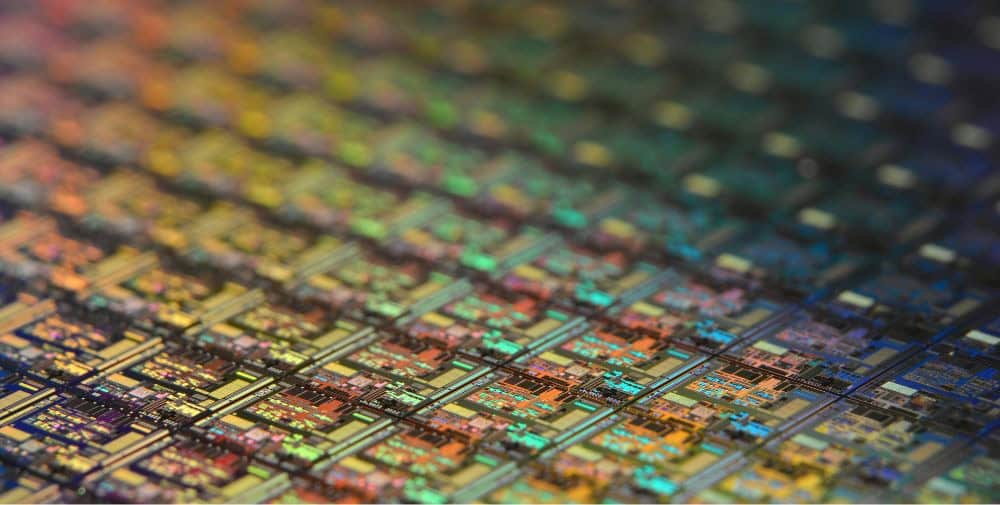

Gallium (chemical abbreviation Ga) has been known for many years in combination with materials from the 5th main group of the periodic table as a so-called III-V semiconductor material (e.g. gallium nitride, gallium phosphide, gallium arsenide). In recent years, it has also been used very successfully in industrial applications.

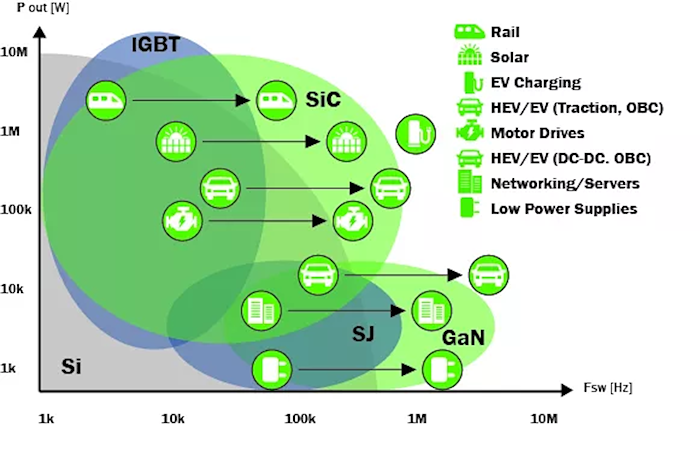

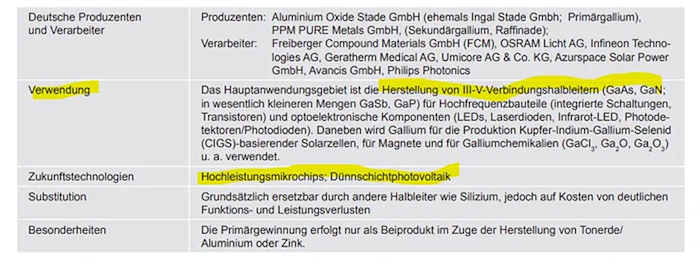

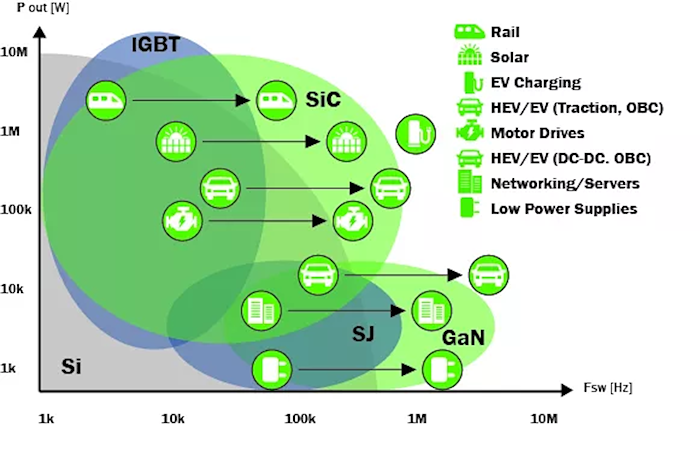

In addition to silicon carbide, gallium nitride in particular is used as a raw material in semiconductor production where the end products, i.e. the corresponding chips, are required in connection with very large currents and/or very high frequencies – i.e. for example in the areas of electromobility or 5G. Greatly simplified, they are much more powerful here, especially in terms of energy efficiency.

A slightly more detailed description of this can be found, as well as the image, which was originally published by OnSemi, one of the players in SiC and GaN, in this article by Nicole Ahner on all-electronics.

The extent to which China itself is ultimately dependent on imports of corresponding products is a matter of dispute. While IFRI still sees a large dependence of China mainly on end products, the country undoubtedly already has players with the necessary competencies in the market, which continues to grow.

Important players on the German side are, for example, Freiberger Compound Materials and Siltronic for wafer production. Among chipmakers, Infineon had most recently underpinned its growth plans in this area with the acquisition of Canada’s GaN Systems.

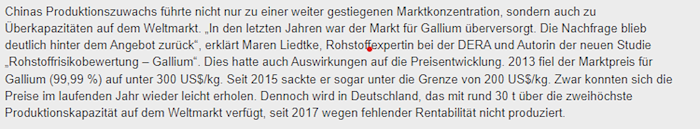

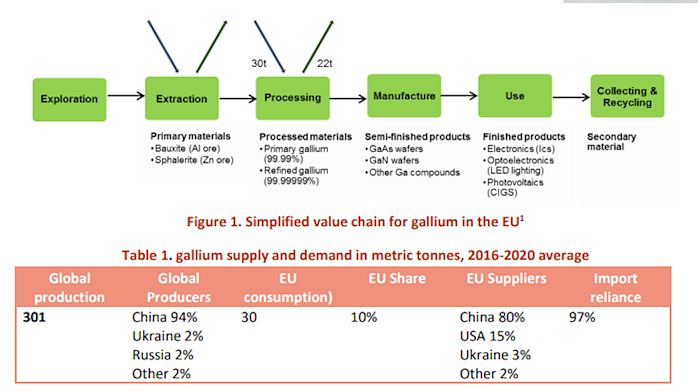

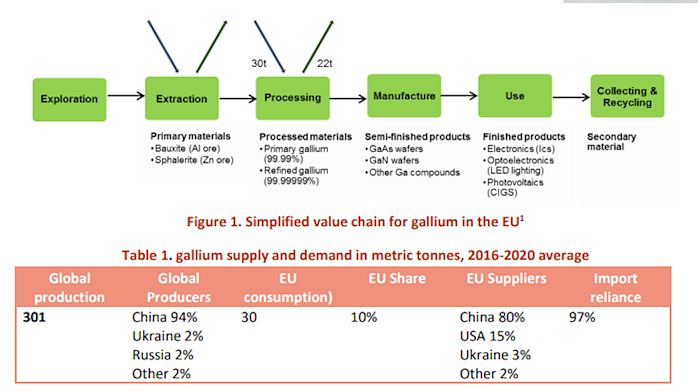

The gallium required for production is obtained on the one hand in raw form, primarily in combination with bauxite (known primarily in connection with aluminum production) (primary gallium), and then processed or purified. Some of it is already being obtained through recycling, for example of defective wafers. Above all, the production or extraction of primary gallium is currently concentrated mainly in China.

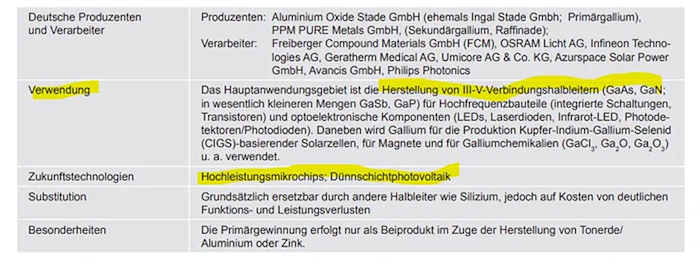

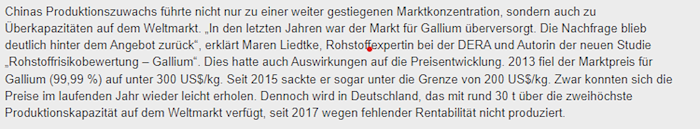

Also in Germany, one is aware of the topic in some places at least since 2016. From this year comes namely a Steckbrief on the subject from the BGR, the Federal Institute for Geosciences and Natural Resources. This sheds light not only on the origin of the material, but also on its use.

BGR and DERA, the German Mineral Resources Agency, therefore also pointed out the risk in a press release.

Particularly interesting in this context is the analysis from 2018.

Even at the EU level, the dependence on primary gallium is nothing new. Information can be found here, for example, on the page of the EU project SCRREEN or the Factsheet on Gallium.

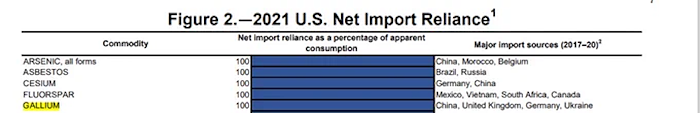

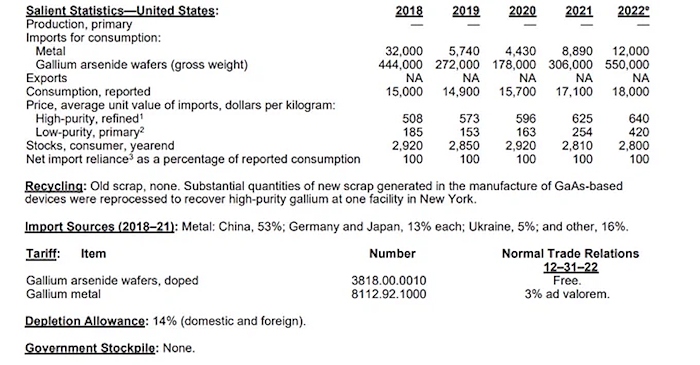

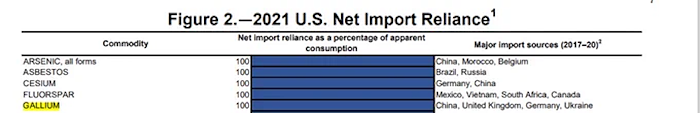

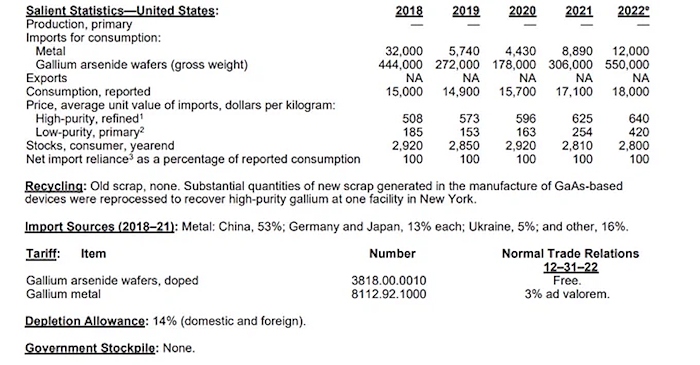

Official documents in the US also point to a 100% dependence on Ga imports, specifically in this document from the U.S. Department of the Interior

Interestingly, Germany is still listed there as an import source, but this may even be due to an outdated database, as the last German gallium production in Stade near Hamburg was discontinued a few years ago.

In principle, however, one is aware of the issue in the U.S. as well, see here the Data from 2023 from the USGS:

Nevertheless, it is exciting that apparently no “government stockpile” exists.

This assessment is based primarily on the fact that gallium nitride (GaN) in particular definitely plays a significant role in military use as well, as these publications from the Department of Defense or the DARPA.

While German and European media have partly attributed the introduction of export controls as a response to tightened export conditions by ASML or as an attack on the EU’s Green Deal, it is undoubtedly an intensification of the so-called chip war essentially waged between the U.S. and China. While in the same-named book by US author Chris Miller (unconditional reading recommendation!), national security plays an essential role in any considerations, the Chinese government is currently arguing along these lines.

What does this mean for global production? In the short term, we will have to wait and see how strict the licensing will be – in the worst case, we can expect significant price increases for corresponding products. In the medium term, it is to be expected that investments will also be made again in gallium production outside China – directly after the announcement, for example, the Belgian-Dutch company Nyrstar had expressed corresponding considerations.

Also in Stade there should certainly be considerations, as well as at some other locations in Europe, where there is currently still an aluminum production.

Conclusion

At the moment one hangs in the primary production of gallium quasi at the Chinese drip, for which now also a regulator was installed. How hard will be regulated remains to be seen. In the sense of the much-invoked de-risking, appropriate capacities should now be built up again as quickly as possible outside China. In terms of economic efficiency, at least a coordinated cooperation between the U.S. and Europe would be desirable.

__________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

This article was first published as part of our NEXT magazine “In Focus: Microelectronics.”

👉 Go to the complete issue of the magazine