During the development of an embryo, cells have the remarkable ability to arrange themselves independently and form the organism into complex shapes – into hands, feet or consistencies such as brain and bones. To better understand the deformations, the research group led by Prof. Otger Campàs (Director of the Cluster of Excellence PoL at TU Dresden and co-author of the study) and Matthew Devlin (UCSB and first author) have found a way to make robotic groupings behave in a material-like manner. They published their findings in the journal Science on February 20, 2025.

“Living embryonic tissues are the ultimate smart materials,” says Campàs. “They have the ability to shape themselves, heal themselves and even control their material strength in space and time.” He and his team discovered that embryos can melt like glass to shape themselves. His work on the physical shaping of embryos was the inspiration to develop a robotic material that is stiff yet strong and can therefore take on new shapes. Previously, when robots were tightly bound together in a group, it was not possible to reshape the collective in such a way that individual parts could change shape fluidly – until now.

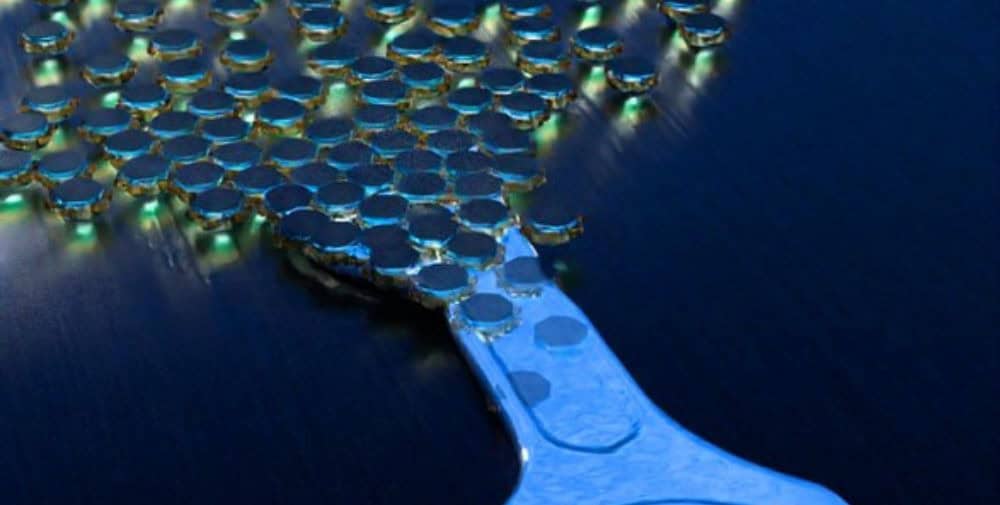

The disk-like, autonomous robots from PoL and UCSB look like small field hockey pucks. They are programmed to assemble themselves into different shapes with different material thicknesses – comparable to the flexibility of embryo cells. Campàs explains: “To form an embryo, the cells in the tissues can switch between liquid and solid states, a phenomenon known in physics as stiffness transitions.”

The researchers then focused on transferring three biological processes from cells to tiny robots:

- active forces that developing cells use to interact with each other so they can move;

- biochemical signaling that allows cells to coordinate their movements in space and time;

- the ability of cells to stick to each other, which ultimately accounts for the rigidity of the organism’s final form.

In the world of robots, magnets are the equivalent of cell-cell adhesion. They encase a robotic unit and allow the robots to cling to each other – at which point the entire group behaves like rigid material. By introducing dynamic forces between the units, the challenge of transforming rigid collectives into deformable materials that mirror living embryonic tissue was overcome: Additional forces as in cells were encoded by tangential forces between the robotic units. Eight motorized gears along the circular exterior of each robot enable this action. By controlling these forces between the robots, the research team was able to enable reconfigurations in otherwise completely rigid collectives. The result: the robot groups reformed.

The biochemical signaling resembles a global coordinate system. “Each cell knows its head and its tail and therefore knows in which direction to apply forces,” explains Elliot Hawkes, Professor of Mechanical Engineering at UCSB. In this way, the cell collective is able to change the shape of the tissue, for example when they line up next to each other and lengthen the body. In the robots, this feat is accomplished by light sensors with polarization filters on the top of each robot: when light falls on the sensors, the polarization of the light determines in which direction the robots must turn their gears and change their shape. “You can just tell them which way to go under a constant light field,” Devlin added.

In this way, the researchers were able to control the group of robots to behave like intelligent material: Parts of the group turned on the dynamic forces between the robots, liquefying the collective, while in other parts the robots simply held on to each other, forming a rigid material. By controlling this behavior across the entire group of robots over time, the researchers were able to create robotic materials that could not only carry heavy loads, but also reshape themselves, manipulate objects and even heal themselves.

Currently, the proof-of-concept robot group consists of only twenty units. However, simulations carried out by Assistant Professor Sangwoo Kim (EPFL) in Campàs’ lab show that the system can be scaled up to a larger number of miniaturized units. “This could enable the development of robotic materials consisting of thousands of units that can take on countless shapes and adjust their physical properties at will, which would change our current concept of objects,” Campàs predicts.

In addition to applications that go beyond robotics, such as the study of active matter in physics or collective behaviors in biology, combining these robotic ensembles with machine learning strategies to control them could yield remarkable capabilities in the field of robotic materials.

Further information

Research group: Matthew R. Devlin, Sangwoo Kim, Otger Campàs and Elliot W. Hawkes

Funding: The study was supported by the National Science Foundation (NSF; Grant 1925373) in the United States of America and the German Research Foundation (DFG) as part of the German Excellence Strategy EXC 2068-390729961 – Cluster of Excellence Physics of Life at TU Dresden.

Original publication: Matthew R. Devlin, Sangwoo Kim, Otger Campàs, and Elliot W. Hawkes (2025): Material-like robotic collectives with spatiotemporal control of strength and shape. Science. DOI: 10.1126/science.ads7942

About the Cluster of Excellence Physics of Life

Physics of Life (PoL) is one of three Clusters of Excellence at TU Dresden. It focuses on identifying the physical laws underlying the organization of life in molecules, cells and tissues. Scientists from the fields of physics, biology and computer science are investigating how active matter in cells and tissues organizes itself into specific structures and gives rise to life. PoL is funded by the German Research Foundation (DFG) as part of the Excellence Strategy. It is a collaboration between scientists at TU Dresden and research institutions in the DRESDEN-concept network, such as the Max Planck Institute of Molecular Cell Biology and Genetics (MPI-CBG), the Max Planck Institute for the Physics of Complex Systems (MPI-PKS), the Leibniz Institute for Polymer Research (IPF) and the Helmholtz-Zentrum Dresden-Rossendorf (HZDR).

– – – – – –

Further links

👉 www.tu-dresden.de

👉 www.physics-of-life.tu-dresden.de

Photo: Brian Long, UCSB