Measuring the world’s smallest magnet

Elementary magnets – the electron spins – whirl at the atomic level. Their orientation upwards or downwards is information. Traditional semiconductor information technologies are only based on the processing of 0 and 1. New technologies such as QuBits have quantum power because each spin can be in a superposition state, i.e. 0 and 1 at the same time. This increases the performance of information processing exponentially. Global research is working on this quantum power and industry is waiting in the wings.

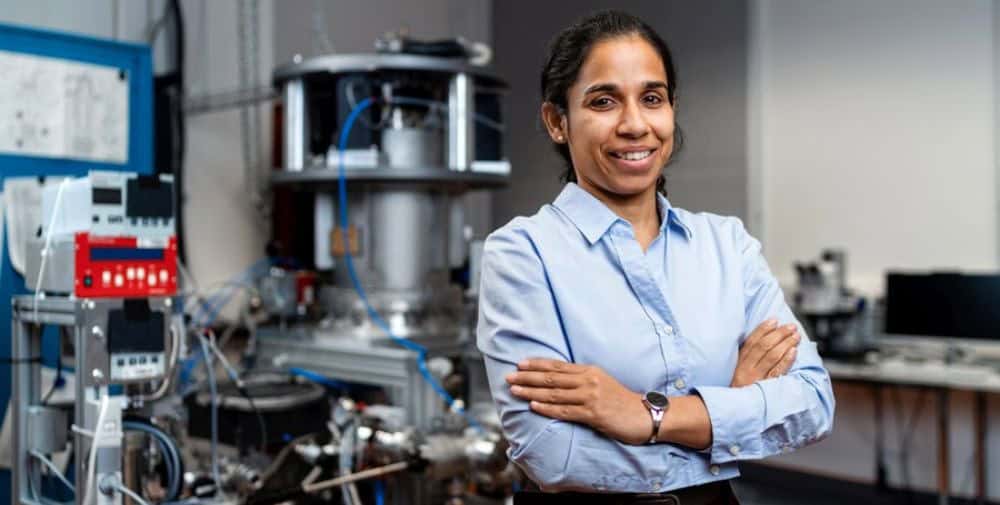

Aparajita Singha is an expert in magnetometry and measures the magnetic moment of a single atom. To do this, she needs a magnetometer, a sample and a special sensor. “To be able to read the information contained in a spin, you first have to measure it,” explains Singha. “My passion for quantum sensors began when I wondered whether I could really measure the world’s smallest magnet.” That was five years ago, when Singha moved from South Korea to Stuttgart. Now she has taken up the professorship for Nanoscale Quantum Materials at the Würzburg-Dresden Cluster of Excellence ctd.qmat in Dresden and has big plans: “In the next five years, I want to measure the world’s smallest magnet together with my team – at room temperature. No one has ever managed that before.”

Nothing works without diamonds

The core of Singha’s measurement technology is a diamond, which she uses as a quantum sensor: “No diamond is perfect. Natural diamonds sparkle even more beautifully the more flaws they have in their chemical structure. We use these flaws as a tool for our research.” To do this, exactly two defects are introduced into a synthetic diamond in the laboratory: first, two carbon atoms are removed from the diamond lattice. Then one defect is filled with a nitrogen atom, while the other remains empty. Together, these two vacancies form the NV center or nitrogen-vacancy center, which acts as a sensor. “Depending on the light emitted by our diamond sensor, we know how strong the magnetic moments of our quantum material are,” says Singha.

The holy grail: measurements at room temperature

Singha still needs low temperatures to measure a single magnetic moment. This is set to change in the next few years. Then these measurements should be possible at room temperature. To achieve this, Singha needs to further develop its technology, both the surface of the diamond, i.e. the sensor, and the material system itself. “This must take place in an absolutely pure environment, as pure as outer space,” she describes. “This precision can only be achieved in an ultra-high vacuum.”

Quantum materials are usually examined under extreme laboratory conditions – ultra-low temperatures, enormous pressure, super-strong magnets. Singha’s method is the only technology that can also work at room temperature: “We are currently still measuring the magnetic fields of individual atoms at -269.15 degrees Celsius (4 K), but we can already manage 100 atoms at room temperature. Our goal is single-spin detection. We are focusing our research on this and developing new diamonds.”

NV centers as a global trend

Measuring individual spins is highly relevant for both basic research and technological applications. As ultra-sensitive sensors, NV centers are already being used worldwide. “The use of NV centers is a global development that is reflected in Saxony. Almost all Saxon quantum start-ups – including those in the new Saxon quantum network SAX-QT – work with defects in diamonds. We are therefore particularly pleased that we have been able to fill the professorship with an expert in this technology. This enriches our research activities in collaboration with Würzburg and gives the local industry more quantum power,” comments Matthias Vojta, Dresden spokesperson for the Cluster of Excellence ctd.qmat.

New quantum professorship for Dresden

Aparajita Singha studied physics in Calcutta and Bombay (India) and then completed her doctorate in Switzerland. She worked as a postdoc in both Switzerland and South Korea. In 2020, she moved to the Max Planck Institute for Solid State Research in Stuttgart. There she began working with NV centers in diamonds. Since 2022, Singha has led an Emmy Noether group researching quantum sensors. On January 1, 2025, Aparajita Singha took up the professorship for Nanoscale Quantum Materials at the Cluster of Excellence ct.qmat in Dresden. She thus strengthens Dresden’s quantum power, which is successfully linked to the Julius-Maximilians-Universität Würzburg via the Cluster of Excellence ctd.qmat. Two postdocs, six doctoral students and one technician work at her professorship. Together, they want to measure the world’s smallest magnet – with diamonds and at room temperature.

ctd.qmat

The Cluster of Excellence ctd.qmat – Complexity, Topology and Dynamics in Quantum Matter at Julius-Maximilians-Universität Würzburg and Technische Universität Dresden researches and develops novel quantum materials with customized properties. Around 300 scientists from more than 30 countries are designing the foundations for the technologies of the future at the interface of physics, chemistry and materials science. In 2026, the cluster entered the second funding period of the Excellence Strategy of the German federal and state governments – with an expanded focus on the dynamics of quantum processes.

Contact

Prof. Aparajita Singha

Cluster of Excellence ctd.qmat

Institute of Solid State and Materials Physics

Technical University of Dresden

Tel.: +49 351 463 42643

E-mail: aparajita.singha@tu-dresden.de

– – – – – –

Further links

👉 https://tu-dresden.de

Photo: Tobias Ritz