Nanomagnets play a key role in modern information technologies. They enable fast data storage, precise magnetic sensors, new developments in spintronics and, in the future, quantum computing. All of these applications are based on functional materials with special magnetic structures that can be tailored and precisely controlled on the nanoscale.

Rantej Bali and his colleagues from the Institute of Ion Beam Physics and Materials Research at the HZDR have already developed methods in the past to imprint tiny magnetic structures in different geometries into materials. This is because the nature of the respective magnetic nanostructures determines how the material behaves in the application. Now the team has taken a decisive step forward: “We have managed to create vertical nanomagnets with a relatively simple material. This can make all technologies that depend on nanomagnets better and cheaper,” reports Bali.

In most materials, the electron spins tend to lie horizontally along the surface and not point outwards. This severely limits their application. The researchers have now been able to show that the spins can be forced to protrude vertically from the material surface by drastically reducing the size of the magnetic areas. Although conventional methods already achieve similar behavior, they have to use starting materials with complex crystal structures or combine different materials in thin layers. This makes these methods complex and expensive. The new development is different: “Both the materials and the production are inexpensive and suitable for most magnetic application scenarios,” explains Bali.

The limitation makes it: Magnetic engraving by ion beam

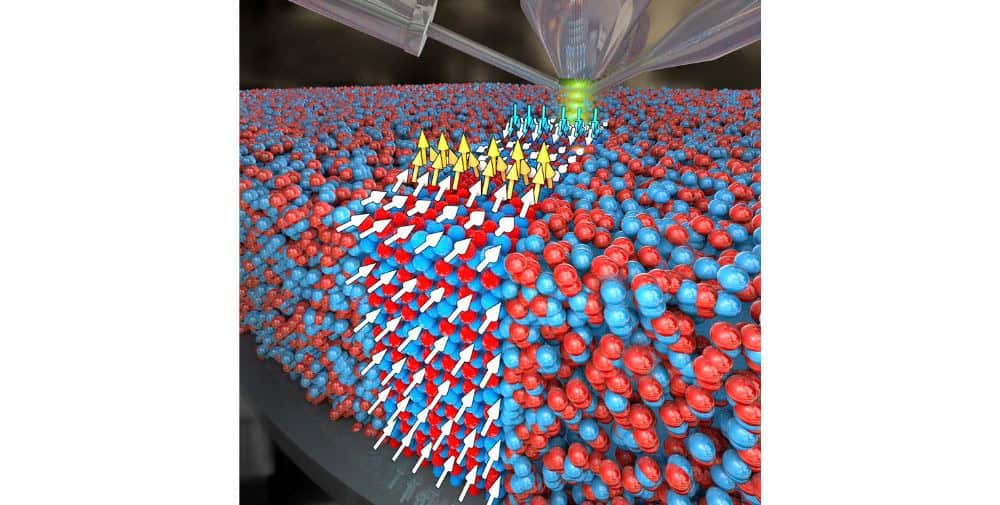

The researchers used a thin metallic film made of an iron-vanadium alloy as the starting material. The atoms of this material are only weakly magnetic in their initially disordered form. However, this changes when bombarded with a highly focused ion beam. The principle: when the beam with a diameter of only around two nanometers hits the material, it rearranges the atoms locally into a crystal lattice. The ions virtually push the atoms into their lattice positions. In the ordered, crystalline state, the material becomes ferromagnetic. This creates tiny magnetic areas in the film piece by piece. Although the exact physical mechanism has not yet been clarified, it is clear that magnetic nanostructures of almost any geometry and size can be created in this way.

In contrast to previous experiments, this time the researchers reduced the width of the nanostrips until they finally obtained extremely thin magnetic areas just 25 nanometres wide. To their surprise, they discovered that in the very thin strips, the nanomagnets suddenly aligned themselves perpendicular to the surface at certain points.

Perpendicular nanomagnets are more efficient

Perpendicular nanomagnets are advantageous for several reasons: firstly, they can be accommodated much more compactly. This increases the data storage density of hard drives, for example, and supports the trend towards ever more miniaturized components. Secondly, they make materials more efficient, for example in spintronics, which uses not only the charge of the electrons but also their spin for signal transport. If an electric current flows through the material, perpendicular moments exert a greater torque on the electrons than parallel ones. Quantum computers can also make use of perpendicular nanomagnets to distinguish between the two possible ground states of a qubit, each of which corresponds to an upward or downward magnetic orientation, and to control them with high sensitivity.

“In a very simplified way, you can think of it like a deck of cards. If you place all the cards next to each other on a table, they take up a relatively large amount of space. If you place them vertically instead, it saves a lot of space. A card that is upright reacts much more sensitively to stimuli from its surroundings than one that is lying flat. The same applies to the reaction of the nanomagnets to external magnetic stimuli,” Bali illustrates.

Experimental and theoretical proof

In order to understand the results of their experiments even more precisely, the researchers conducted further experiments to observe how magnetic domains formed in the material. These are areas in which all magnetic moments are aligned in the same way. If two opposing domains collide, the magnetization has to move into the narrow boundary area, the domain wall, which is only a few nanometres wide. The result: the magnetic moments align vertically.

The HZDR team was initially able to demonstrate this particular twist using magnetic force microscopy and stray fields. The NTNU team led by Magnus Nord in Trondheim, Norway, measured the finished material again using the so-called differential phase contrast method. This method provides nanoscale images that show how electrons react when passing through magnetic areas. This enabled the researchers to map the magnetization of the strips in two dimensions and make the boundary areas of different magnetic domains visible. The team led by Michal Krupinski from the Institute of Nuclear Physics at the Polish Academy of Sciences in Kraków supplemented theoretical simulations and contributed the visualization, which show how precisely the domain boundaries force the magnetic moments into the vertical. The teams now want to build on the joint new findings to further develop technologies for magnetic memories, sensors and spin-based quantum computing in the future.

Publication

M. S. Anwar, I. Zelenina, P. Sobieszczyk, G. Hlawacek, K. Tveitstøl, K. Potzger, J. Fassbender, O. Hellwig, J. Lindner, M. Krupiński, M. Nord, R. Bali, Confinement Driven Spin-Texture Evolution in Directly Written Nanomagnets, in Advanced Functional Materials, 2025, (DOI: 10.1002/adfm.202513904)

Contact

Dr. Rantej Bali

Institute of Ion Beam Physics and Materials Research at the HZDR

Tel.: +49 351 260 2461 | E-Mail: r.bali@hzdr.de

– – – – – –

Further links

👉 www.hzdr.de

Picture: Sander Münster/HZDR